Period Style Ultra Luxury Custom Homes, Villas and Estates by design

Establishing Period Style

Plan for your Dream Home now!

Click: Order Planning e-book or CD here!

Excerpt from Creating the Custom Home.

To order this hyperlinked CD rom go to CD's/ Books. To go to a comprehensive listing of reference books concerning the history and evolution of the private residence and related works go to Bibliography.

-

"Boxy, but Good" is an essay describing the benefits of simple geometry in the layout of the floor plan, as created by prominent Renaissance architects, with applications to today's custom homes.

-

"Millennial Architecture, Traditionalism, and The American Luxury Home"anticipates the future by examining the past.

-

"A Not So Big Idea": Why the "Not So Big" approach is not complete nor accurate in its assessment of American lifestyle, space needs, style trends, nor cost trade-offs.

-

Disney's Celebration: Another Stepford? New Urbanism failure.

-

"The New Cultural Urbanism" with John Henry and Allan Banks, television feature. (no longer online)

On Re-creating Period Architectural Styles: To be or not to be historically 'correct'

'Period Style’ is usually a referent to historical styles based on Greco-Roman or gothic motifs developed after the Renaissance. Technically the term can be used to identify any architectural production from antiquity to current fashion dated by either a unique artistic and/ or material innovation usually associated with a historical period and its social, cultural or political system. Period style has had a negative connotation among modernist theorists since it implies an unoriginal adaptation of a previously established way of designing and building, prior to of course the dawn of the Modern Movement.

Modernism

That all contemporary architecture should be ‘of our time’ is a postulate of modernist thinking, meaning that architects must use only the latest industrial materials production and the appropriate construction applications, to solve the exigent ‘problem’ or programmatic spatial/building requirements. The result can only be a logical, rational form. This ‘architecture’ of pure function is not, and can not, be arbitrary; it cannot be based on a priori aesthetic principles or composition. Beauty, if possible, is the result of a mechanical process that has been distilled so that all architects can apply the same process to all programs to produce similarly appropriate results. This methodology has produced the occasionally strikingly bold and original signature piece by leading practitioners but has left in the main a legacy of mediocre to barbarically insensitive works in the residential and commercial sphere. Mass production techniques cut out any contribution by individual artisans except for the simplest trimming of details. And if we must rely only on the latest materials and processes (machine made glass, steel, plastics, ferro-concrete, etc.) when is the cut off date for what is permitted --1840, 1940, 1980, last month, last year, last week, or yesterday?

Classicism

By

the moderns’ thinking, all architecture that refers to classical

influence of any type therefore is necessarily ‘not of our time’, an

archaeological vestige unworthy intellectually at least, and not

fitting for reproduction in any form or for any reason. The classicist

view is that a three thousand year tradition cannot be abrogated by

any pseudo-intellectual argument, albeit in the instances of

expediency allowing minor movements that stray from this tradition for

only a short period of time (for example, fulfilling a housing and

infrastructure shortage at the end of world wars) and that eventually

in times of peace and fruition a turning to the ‘people’s art’ is

inevitable; that architecture is a public art more than a private one;

that civitas must be maintained between the individual and the public

realm, and that a fitting architecture has evolved and is in place

which offers a complete vocabulary – an eternal language – suitable to

fulfill practically all the urban, commercial, public and private

building needs of succeeding generations.

By

the moderns’ thinking, all architecture that refers to classical

influence of any type therefore is necessarily ‘not of our time’, an

archaeological vestige unworthy intellectually at least, and not

fitting for reproduction in any form or for any reason. The classicist

view is that a three thousand year tradition cannot be abrogated by

any pseudo-intellectual argument, albeit in the instances of

expediency allowing minor movements that stray from this tradition for

only a short period of time (for example, fulfilling a housing and

infrastructure shortage at the end of world wars) and that eventually

in times of peace and fruition a turning to the ‘people’s art’ is

inevitable; that architecture is a public art more than a private one;

that civitas must be maintained between the individual and the public

realm, and that a fitting architecture has evolved and is in place

which offers a complete vocabulary – an eternal language – suitable to

fulfill practically all the urban, commercial, public and private

building needs of succeeding generations.

Post-Modernism

"My hope is that our reluctance to abandon traditional architecture in our homes will lead us back to a re-examination of the classical tradition in our civic life as well." Alvin Holm

This recent (15-20 year) movement was based on

a prevailing political and social change towards plurality in personal

and artistic expression. If modernism was perhaps extreme in its

agenda, then other views were permitted, even the invocation of

precedent. At the beginning, the practitioner who included classical

elements in his or her work risked censure by the status quo theorists

and architectural critics, so such examples had to be packaged with

‘irony’ or intellectual apologetics – exaggerations, purposely out of

scale elements, ‘playful’ concoctions, irrational arrangements of the

architectural elements, etc. – to soften the academic backlash. In

reality, postmodernism was a response to a call to end or modify the

strict dogma of modernism; it was the first step to assuage a

disenfranchised public, one that was tired of modernism’s incessant

banalities hiding behind a metaphysical curtain. No more blank walls

and soulless concrete and glass. No more boxes, no more extruded

diagrams.

The parallel thinking in philosophy and social science has produced a cultural relativism that is reflected in our current architecture. The production of idiosyncratic works with 'quotation', 'irony', etc.where there is 'no necessary connection between the signifier and the signified, between spoken word and object' (Derrida) has led to unstudied compositions leading to further bizarre works of deconstruction. No rules, no process, no building on achievements generally considered sine qua non in previous generations -- only the unfettered search for the new, the sensational: to be of the moment.

-- "that way madness lies." Christopher Norris

Status Quo

The problem now is that an insatiate and slowly re-educated public is demanding more than the profession is capable of delivering: period work that is authentic in spirit, style, and detail. The postmodern architect – meaning almost all architects practicing today – has had little or absolutely no training in the creation of classical or gothic architecture, the root form of period work. There was no teaching on basic theory except in describing a dry progression from the Egyptian pyramids to the Paris opera, and this has been only in the past 20 years. Walter Gropius, Bauhaus initiate and Harvard professor in the early half century, insisted on "starting from zero". The profession is ignorant, inept -- the academic world only softening their implacable stance on attempting any approach towards teaching the breadth of classical architectural theory. To practice serious period work now entails personal research and study, observation, and steady practice. To pretend otherwise proves folly with usually ridiculous outcomes.

The architect, who employs period elements then, is drawing on tradition

to design for current needs and wishes. Whenever we design and build

projects offering ‘original’ works, it is only disingenuous to claim an

ignorance of all that preceded; it is stupidity to purposefully ignore

the great works of the classical past. Every architectural work is a

period piece unless our definitions of gravity, windows and doors, walls

and roofs, floors and ceilings have changed -- or change from day to

day. We always build variations or near copies of what were built

before. Anything else is anti-architecture: deconstruction is one such

manifestation.

The architect, who employs period elements then, is drawing on tradition

to design for current needs and wishes. Whenever we design and build

projects offering ‘original’ works, it is only disingenuous to claim an

ignorance of all that preceded; it is stupidity to purposefully ignore

the great works of the classical past. Every architectural work is a

period piece unless our definitions of gravity, windows and doors, walls

and roofs, floors and ceilings have changed -- or change from day to

day. We always build variations or near copies of what were built

before. Anything else is anti-architecture: deconstruction is one such

manifestation.

Consider

a writer or playwright, or even a musician who must invent a

completely different language, notation or script upon writing or

composing successive works in order to claim originality. Such a

notion is absurd. One uses the same language with proper syntax to

communicate to his audience but tell a different, or slightly

different, story. The syntax of column and wall, pitched roof, porch

and arcade, beam and arch – and the multitude of evolutionary original

variations -- has been concretized over four millennia and remains

still the vital source, inspiration and model for any contemporary

work, period or modernistic. Whether one builds of wood, stone, or

steel the component pieces remain the same, the ideal model is intact.

One can strip away the decorative work that embellishes, the vestigial

bands, trim, and moldings necessary to articulate and join the parts,

but in the end the syntax remains. Consider, for example, how similar

the multistoried Palazzo Farnese resembles the modern mid-rise office

block, especially now that ribbon glass is being minimized for energy

conservation. Moreover, why does modern steel construction resemble

the timber frame in its layout and principles of connection?

Consider

a writer or playwright, or even a musician who must invent a

completely different language, notation or script upon writing or

composing successive works in order to claim originality. Such a

notion is absurd. One uses the same language with proper syntax to

communicate to his audience but tell a different, or slightly

different, story. The syntax of column and wall, pitched roof, porch

and arcade, beam and arch – and the multitude of evolutionary original

variations -- has been concretized over four millennia and remains

still the vital source, inspiration and model for any contemporary

work, period or modernistic. Whether one builds of wood, stone, or

steel the component pieces remain the same, the ideal model is intact.

One can strip away the decorative work that embellishes, the vestigial

bands, trim, and moldings necessary to articulate and join the parts,

but in the end the syntax remains. Consider, for example, how similar

the multistoried Palazzo Farnese resembles the modern mid-rise office

block, especially now that ribbon glass is being minimized for energy

conservation. Moreover, why does modern steel construction resemble

the timber frame in its layout and principles of connection?

In the residential field, the penchant for modern or postmodern work

appeals to a very slight minority. Throughout the changing mainstream

of artistic production this century on canvas, with sculpture, film or

music, the form of the house has remained relatively constant. Only

when the simple house is elevated to villa, palace, or mansion [Def:

Middle English, a dwelling, from Old French, from Latin mânsio,

mânsion-, from mânsus, past participle of manêre, to dwell, remain.]

does style become a conscious objective. Otherwise, one builds in the

vernacular. The vernacular form can mutate of course or disappear

completely through neglect or more likely, from outside influence

(style mongers) or for reasons of cost and affordability.

In the residential field, the penchant for modern or postmodern work

appeals to a very slight minority. Throughout the changing mainstream

of artistic production this century on canvas, with sculpture, film or

music, the form of the house has remained relatively constant. Only

when the simple house is elevated to villa, palace, or mansion [Def:

Middle English, a dwelling, from Old French, from Latin mânsio,

mânsion-, from mânsus, past participle of manêre, to dwell, remain.]

does style become a conscious objective. Otherwise, one builds in the

vernacular. The vernacular form can mutate of course or disappear

completely through neglect or more likely, from outside influence

(style mongers) or for reasons of cost and affordability.

Present period work on the whole is inaccurate, sloppy, and often farcical or grotesque. This is a problem due simply to a lack of an in-depth education of the orders and theories of proportion and composition (terms outlawed by the modernists) by registered architects, and the even more unfortunate circumstance of the suburban house culture in the main, where over 90% of the residential landscape is designed by in-house draftspersons of large production builders and ‘residential designers’ accepting custom home commissions, whose backgrounds are nearly completely devoid of any theoretical instruction concerning period design. Even for the aspiring classicist or period architect or designer, the direct link with academia or a 'master' in which the tradition is properly understood is not possible.

Greco-Roman and Gothic models

As

mentioned at the beginning, we usually refer to period style work

derived from the Greek and Roman example that was developed throughout

Europe following the Renaissance. When we speak of French, Italian,

Mediterranean, English, Dutch, etc. period style, we are recollecting

the post-Renaissance architecture typical of a certain country and

time of history. Nevertheless, it is not that easy to categorize the

period because art is constantly changing from generation to

generation, even within a lifetime.

As

mentioned at the beginning, we usually refer to period style work

derived from the Greek and Roman example that was developed throughout

Europe following the Renaissance. When we speak of French, Italian,

Mediterranean, English, Dutch, etc. period style, we are recollecting

the post-Renaissance architecture typical of a certain country and

time of history. Nevertheless, it is not that easy to categorize the

period because art is constantly changing from generation to

generation, even within a lifetime.

Art and architecture may evolve to a high point, then

plunge to a limbo before being both rediscovered and revived or

forever dying out. Extinction of a culture usually spells an end of

its art. Egyptian art and architecture is chronologically specific but

after the might of its latter kingdoms waned found its artistic

heritage barely appreciated outside its borders. The Cretan kingdom

was wiped out by earthquake and tidal wave; the artifacts at Knossos,

especially the inverted column, are not to be found elsewhere .

The Etruscan people practically vanished with their architecture.

Fortunately, the Romans appreciated the remains of the once proud

Athenian acropolis and the colonial Ionians enough from which to grow

their unique buildings of brick, mortar and stucco as well as hand

hewn stone. However, after half a millennium of conquest and glory

their protracted defeat by the Goths threw their masterworks into

obscurity and ruin. Another thousand years passed before the great

temples, forums, amphitheaters, and baths were rediscovered and

measured, rebuilt and restored forming the pure models for classical

revivals henceforth. The intervening latter period, the Romanesque

(consisting of Roman and Byzantine styles of the 11th and 12th

centuries), offers a wealth of detail and beauty that inspired Florida

architect Addison Mizner in the 1920’s to combine Tuscan stone, stucco

and tile roofs in creating a unique Mediterranean period style

residential architecture. Architects of subsequent generations share

the same privilege.

.

The Etruscan people practically vanished with their architecture.

Fortunately, the Romans appreciated the remains of the once proud

Athenian acropolis and the colonial Ionians enough from which to grow

their unique buildings of brick, mortar and stucco as well as hand

hewn stone. However, after half a millennium of conquest and glory

their protracted defeat by the Goths threw their masterworks into

obscurity and ruin. Another thousand years passed before the great

temples, forums, amphitheaters, and baths were rediscovered and

measured, rebuilt and restored forming the pure models for classical

revivals henceforth. The intervening latter period, the Romanesque

(consisting of Roman and Byzantine styles of the 11th and 12th

centuries), offers a wealth of detail and beauty that inspired Florida

architect Addison Mizner in the 1920’s to combine Tuscan stone, stucco

and tile roofs in creating a unique Mediterranean period style

residential architecture. Architects of subsequent generations share

the same privilege.

Evolution of the Periods

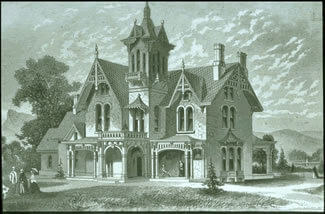

As each European country of the 15th and 16th centuries interpreted the Renaissance interest in Greek and Roman art and architecture, they had to build on or reject the unique architecture that was already in place -- that termed Gothic originating in Norman France. The Romans viewed the Goths as barbarians; their architecture was likewise despised. Thus began a rift between the antique classical tradition of Greece and Rome against the 'modern' gothic style (a unique method of stone construction which lasted for nearly 400 years before being revived in the 19th century), a rift which threw academics and practitioners into theoretical polemics again and again during the 17th through 19th centuries. [Our current housing styles overall tend toward the gothic derivative as interpreted by the Victorians: the free plan and its resultant irregular roofline.]

The state architecture of Greece and Rome was adapted for public

and private commercial structures in urban centers and for palaces for

royalty and the wealthy merchant class, while the villa form popula rized

by Palladio seized the imagination of those who would build in the

country and suburbs. The French kept their gothic tradition at first

grafting the stylish Renaissance features, but eventually accepting

the Italian pure form -- with some modifications, notably the steeper

rooflines. While the Italian Renaissance was clearly a revival of the

Roman republican and imperial type (the 14th- 15th century Italian

artist/ architect/ builder had meager means to explore the Aegean

Hellenic marble and stone temples), it was only in the early 19th

century that archeological record was available to the architect

desiring to correctly emulate the pure Grecian type, on which the

Romans believed was their basis.

rized

by Palladio seized the imagination of those who would build in the

country and suburbs. The French kept their gothic tradition at first

grafting the stylish Renaissance features, but eventually accepting

the Italian pure form -- with some modifications, notably the steeper

rooflines. While the Italian Renaissance was clearly a revival of the

Roman republican and imperial type (the 14th- 15th century Italian

artist/ architect/ builder had meager means to explore the Aegean

Hellenic marble and stone temples), it was only in the early 19th

century that archeological record was available to the architect

desiring to correctly emulate the pure Grecian type, on which the

Romans believed was their basis.

As each country’s architects compared their vernacular works to the Renaissance discovery of Roman architecture, distinct personal interpretation and invention – a combination of craft and education – was woven together that left distinct imprints per house, city and town. The Renaissance ‘period’ then has to be further subdivided into the various countries in Europe that aspired to integrate the ancient way of building into their current architectural practices which was based at that time, in the 14th and 15th centuries, on gothic and Romanesque form. The gothic manner of building, as a major architectural phenomenon, developed nonetheless completely on its own track before fading away toward the end of the 18th century.

The gothic and classical modes, although theoretically completely opposite in style and composition, form, engineering, etc., were either combined in varying degrees as each architect was moved in the ensuing centuries (an eclectic motive), or were archaeologically duplicated in exterior form and major detail, while serving modern needs. Revivals of these two primary roots of the Western Tradition continued after the Renaissance to contemporary times, each having its major and minor recurrences, the major ones termed Neo-classical or Victorian, Greek Revival or Gothic Perpendicular for example. The appreciation for both models has never faded in spite of modernist experimentation. And architects to this day attempt ‘period style’ revivals of their own, one project at a time, at their clients’ bidding. The question remains: how good are these revivals: can contemporary architects, builders, and craftspersons design and execute the work in an authentic manner?

Identifying the Periods

In attempting to identify period styles in architecture, and to

realize the difficulty involved, we need only to examine the Egyptian

evolution in art and architecture to understand that within each

country’s historical development, the archaeologist may identify

distinct shifts in form, craftsmanship, decorative effects, scale and

type. The history of Egypt includes several dynasties ruling over

3,000 years among which the earliest are deemed artistically superior,

while the latter show dissolution. It can be confirmed that Egypt

enjoyed its own Renaissance, much like that of the United States

commonly figured at the turn of the century. Attempting an Egyptian

period style makes about as much sense as trying to build in the

American period or French, English or Italian. Clearly further

subdivisions are necessary. The English Tudor style, for example, was

an artistic development paralleling the ruling dynasty begun by Henry

VII until Elizabeth I, a period of about 118 years. The Tudor style

evolved during that time and can be accurately described as

In attempting to identify period styles in architecture, and to

realize the difficulty involved, we need only to examine the Egyptian

evolution in art and architecture to understand that within each

country’s historical development, the archaeologist may identify

distinct shifts in form, craftsmanship, decorative effects, scale and

type. The history of Egypt includes several dynasties ruling over

3,000 years among which the earliest are deemed artistically superior,

while the latter show dissolution. It can be confirmed that Egypt

enjoyed its own Renaissance, much like that of the United States

commonly figured at the turn of the century. Attempting an Egyptian

period style makes about as much sense as trying to build in the

American period or French, English or Italian. Clearly further

subdivisions are necessary. The English Tudor style, for example, was

an artistic development paralleling the ruling dynasty begun by Henry

VII until Elizabeth I, a period of about 118 years. The Tudor style

evolved during that time and can be accurately described as

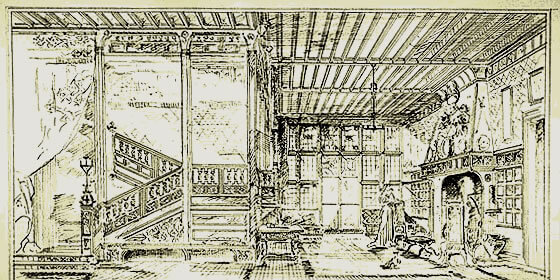

"…a transitional style between Gothic Perpendicular and Palladian. Manor houses, built for the new trading families, exhibit the style's characteristics of greater domesticity and privacy: rooms multiplied as the great hall's importance diminished; oak-paneled interiors had plaster relief ornament; furniture increased. Exteriors showed modified perpendicular features, e.g., square-headed, mullioned windows. Brickwork combined with half-timber, high pinnacled gables, and numerous chimneys to create a distinctive look. Principal Tudor examples are parts of Hampton Court Palace (begun 1515) and some colleges of Oxford and Cambridge."

Notice that this dictionary definition includes comments relating to

lifestyle (domesticity and privacy), the floor plan or layout (number

of rooms, sizes, and change in use), the interior details (oak panel

and plaster ornament), interior furnishings (an increase in permanent

fixtures), the exterior form (perpendicular geometry), the

fenestration (square-headed mullioned windows), the exterior materials

(brickwork and half-timbering), and the roofline (pinnacled gables and

numerous chimneys).

Notice that this dictionary definition includes comments relating to

lifestyle (domesticity and privacy), the floor plan or layout (number

of rooms, sizes, and change in use), the interior details (oak panel

and plaster ornament), interior furnishings (an increase in permanent

fixtures), the exterior form (perpendicular geometry), the

fenestration (square-headed mullioned windows), the exterior materials

(brickwork and half-timbering), and the roofline (pinnacled gables and

numerous chimneys).

Establishing the Period: Materials, Planning, Composition and Detail

Such an examination as above is necessary to define the essential

ingredients of a period. The overall layout is specific to a period.

It reflects the lifestyle of its occupants per that time. The status

of the homeowner is evident by the scope of construction, the expense

of materials, the quality of the work, the level of elaboration in its

decorative effects. The architecture of the king’s castle is different

from the Lord’s manor, which is still larger and more elaborate than

that of the lowly merchant’s townhouse, etc. So even within a period,

domestic, public and private buildings may have varying

characteristics. The elements that are most similar among all are

generally used to identify the period.

Such an examination as above is necessary to define the essential

ingredients of a period. The overall layout is specific to a period.

It reflects the lifestyle of its occupants per that time. The status

of the homeowner is evident by the scope of construction, the expense

of materials, the quality of the work, the level of elaboration in its

decorative effects. The architecture of the king’s castle is different

from the Lord’s manor, which is still larger and more elaborate than

that of the lowly merchant’s townhouse, etc. So even within a period,

domestic, public and private buildings may have varying

characteristics. The elements that are most similar among all are

generally used to identify the period.

We can note how kitchens are often separated from formal areas and completely segregated into separate structures. Why is this? Because the slaughter of animals and cooking odors was offensive and the fear of fire from multiple pits and ovens could spread to engulf the living quarters. Even townhouses of Tudor times had separate kitchens and outhouses, a feature that prevailed until the 19th century.

The

plan will reveal how close farm animals, stores, and servant’s

quarters are set to the owner’s private apartments. We can see how

large the separate rooms came to be relative to each other, how that

built-in closets were not in use, but rather chests and armoires which

were carried back and forth from other residences. Secret passageways,

the separation of staff persons, stables, armories, sick rooms,

anterooms, etc. can be identified per period.

The

plan will reveal how close farm animals, stores, and servant’s

quarters are set to the owner’s private apartments. We can see how

large the separate rooms came to be relative to each other, how that

built-in closets were not in use, but rather chests and armoires which

were carried back and forth from other residences. Secret passageways,

the separation of staff persons, stables, armories, sick rooms,

anterooms, etc. can be identified per period.

The materials for construction: how the stone is cut, which coloration and type of roofing is employed, the finishing and textural finishes, the handling of wood and trim, the application of plaster detailing, moldings and paneling, are all indicators of a particular period. The height and breadth of rooms, whether or not they corresponded to specific ratios, the flooring materials, ceiling decoration, amount of gilding, window types and general design, also point to a specific period.

Period Interiors

Period interiors are difficult to establish when it comes to

furnishings and accessories. The interior architecture normally

remains intact, although subsequent remodelings, to keep up with

current fashion, change the interior style in regards to moldings,

trim, decorative paneling, and ceiling treatments even making it at

times impossible to determine what came first without going backwards

through the layers. Mary Gilliatt (Period Style) points out the

problem of determining the associated interior decoration:

Period interiors are difficult to establish when it comes to

furnishings and accessories. The interior architecture normally

remains intact, although subsequent remodelings, to keep up with

current fashion, change the interior style in regards to moldings,

trim, decorative paneling, and ceiling treatments even making it at

times impossible to determine what came first without going backwards

through the layers. Mary Gilliatt (Period Style) points out the

problem of determining the associated interior decoration:

"Unless you are a specialist in the style of decoration associated with different periods it can be confusing to distinguish between, or even to recognize, the various components that together form a particular style. Apart from the interiors depicted in early paintings (notably those from the Dutch and Flemish schools) and the domestic settings which can be glimpsed in the backgrounds of early portraits, there is very little record of what interiors were really like before the latter part of the eighteenth century."

Architects and interior designers normally matched the style of

exterior architecture to that of the interior until exotic

contrapositions and the introduction of different period treatments,

rather than maintaining a single unifying style throughout, became

fashionable. This change became widespread during the eclectic

variations of the 19th century. Period style came under repeated

attack, as academics yielded to the wild experimentation

characterizing a century when no single style could claim preeminence.

Architects and interior designers normally matched the style of

exterior architecture to that of the interior until exotic

contrapositions and the introduction of different period treatments,

rather than maintaining a single unifying style throughout, became

fashionable. This change became widespread during the eclectic

variations of the 19th century. Period style came under repeated

attack, as academics yielded to the wild experimentation

characterizing a century when no single style could claim preeminence.

A reaction against the stricture of symmetrical classicism on the interior disposition of rooms eventually led to the adoption of the gothic based ‘picturesque’ or romantic mode characterized in smaller domestic structures. Palaces, hôtels, and grand manors however seemed to retain the Renaissance French and Italian influences as interpreted by the expression of Beaux-Arts masters in the late 17th through 19th centuries. But the loose and free layout of interior space was eagerly adopted by the Victorians whose spirit we have incorporated in our time for nearly all our domestic architecture, modern (contemporary) as well as bastardized classical.

Period Exteriors

The elevations that correspond to the plans are considered more

telling in setting the period. An elevation that is symmetrical is

usually based on the Greco-Roman model. The temple front is the

definitive element. The gothic is generally asymmetrical when applied

to domestic work (most of the main cathedrals were symmetrical

excepting their towers, often completed by different masons at

different times, or asymmetrical due to

expansion or initial construction respecting irregular adjacent

structures). Is the structure set on a plinth or pedestal base? Are

there columns supporting arches or a straight entablature? Is the

workmanship and detailing medieval, neo-classical, or Victorian? And

are we speaking of American Victorian or British Edwardian? Are the

columns proportional according to the Orders described by Vitruvius or

is there some liberty in their ratio of width to height, the spacing

between each intercolumniation, and could the voussoirs of the arches

point to Art Nouveau or Art Deco perhaps?

The elevations that correspond to the plans are considered more

telling in setting the period. An elevation that is symmetrical is

usually based on the Greco-Roman model. The temple front is the

definitive element. The gothic is generally asymmetrical when applied

to domestic work (most of the main cathedrals were symmetrical

excepting their towers, often completed by different masons at

different times, or asymmetrical due to

expansion or initial construction respecting irregular adjacent

structures). Is the structure set on a plinth or pedestal base? Are

there columns supporting arches or a straight entablature? Is the

workmanship and detailing medieval, neo-classical, or Victorian? And

are we speaking of American Victorian or British Edwardian? Are the

columns proportional according to the Orders described by Vitruvius or

is there some liberty in their ratio of width to height, the spacing

between each intercolumniation, and could the voussoirs of the arches

point to Art Nouveau or Art Deco perhaps?

The

pitch of roof, height and width of windows, handling of stone and

decorative trim elements, design of chimneys, proportion of wall to

window, all combine to create a particular period style. The ratio of

wood siding and trim to stone or brick is important. The size of the

individual masonry units, how deep the mortar bed happens to be, how

the joints are pointed, and in which pattern they are laid, all add up

to a specific style. Are the windows casement types or single or

double hung, etc.?

The

pitch of roof, height and width of windows, handling of stone and

decorative trim elements, design of chimneys, proportion of wall to

window, all combine to create a particular period style. The ratio of

wood siding and trim to stone or brick is important. The size of the

individual masonry units, how deep the mortar bed happens to be, how

the joints are pointed, and in which pattern they are laid, all add up

to a specific style. Are the windows casement types or single or

double hung, etc.?

Signature Style

Period style can be attributed to individual architects and

interior designers even. Artisans as well as architects traveled

across borders, allowing further distinctions. Italian architects were

invited to remain at court in France and England. English architects

were employed in Russia. Palladio’s work com prised

an identifiable style that was disseminated throughout Europe via his

‘plan book’ Quattro Libri dell’Architettura, published in 1570. We can

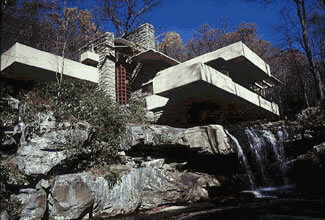

speak of Miesian, Corbusian, Wrightian, and Michaelangelesque styles.

In the case of Wright, we have to inquire of which time in his life we

are seeking a particular effect. His early Prairie style houses are

different from the International Style of Fallingwater or the later

Modernist Guggenheim museum. His very first secret commissions while

working for Adler and Sullivan were in fact period style colonial

revival and Tudor styles! Now we can ask for a Mark Hampton interior

or Gehryesque design. We know each individual stands for a particular

point of view while their oeuvre has been well publicized.

prised

an identifiable style that was disseminated throughout Europe via his

‘plan book’ Quattro Libri dell’Architettura, published in 1570. We can

speak of Miesian, Corbusian, Wrightian, and Michaelangelesque styles.

In the case of Wright, we have to inquire of which time in his life we

are seeking a particular effect. His early Prairie style houses are

different from the International Style of Fallingwater or the later

Modernist Guggenheim museum. His very first secret commissions while

working for Adler and Sullivan were in fact period style colonial

revival and Tudor styles! Now we can ask for a Mark Hampton interior

or Gehryesque design. We know each individual stands for a particular

point of view while their oeuvre has been well publicized.

In recent years it is clearer that within movements and periods, the work of the individual architect becomes the defining element. So within the Modern movement, Mendellshon is markedly different than Gropius, the Russian structuralists vary from the Italian futurists, Paul Rudolph is not quite like Richard Meier; the Postmodernists have Michael Graves and the late Charles Moore sharing irony but not quality, Robert Stern’s and Ricardo Bofil’s attention to authenticity is not as academic as Allen Greenberg’s. The architect for Louis XVI handled frou-frou differently from his predecessor the XIV. The latter style is less flamboyant. Henry V’s apartments do not share the decorative flair of Henry VIII’s, as the royal quarters of Elizabeth I begin to be influenced by the new modern style of the Renaissance.

Creating the Period Home

It

is obvious that our notions and understanding of period style elements

are barely accurate. This is due simply to a lack of proper education.

The level of detail and proper dissemination of classical and gothic

theory and practice is not found in the architectural curricula of

most U.S. universities or even abroad (since almost all have yielded

completely to the modern movement). Most architects must have to

either travel abroad to witness first-hand the fine details,

workmanship, and overall applications, or worse (since it is truly

'third generation') -- visit colonial to pre-40’s work in this country

to witness the best examples, and/ or to rely wholly on reference

books, which fortunately are in ever increasing supply as relates to

historical and period architecture of all types. Only two or three

U.S. universities offer comprehensive courses in classical

production. We have a hazy idea about our ‘French country’, ‘English

Tudor’, ‘Mediterranean’, and ‘Contemporary’ styles, at least what the

recent spate of fashion designers interpret for our digestion. That

they are mostly woefully inadequate in proper execution is deplorable.

The fact remains that good period work is more costly and time

consuming to recreate than the half-baked 'transitional' styles

filling in. So little is produced that is truly first rate. Our

current ‘custom’ homes, generally merchant built notwithstanding, are

greatly distilled and stripped-down variations of true period

architecture.

It

is obvious that our notions and understanding of period style elements

are barely accurate. This is due simply to a lack of proper education.

The level of detail and proper dissemination of classical and gothic

theory and practice is not found in the architectural curricula of

most U.S. universities or even abroad (since almost all have yielded

completely to the modern movement). Most architects must have to

either travel abroad to witness first-hand the fine details,

workmanship, and overall applications, or worse (since it is truly

'third generation') -- visit colonial to pre-40’s work in this country

to witness the best examples, and/ or to rely wholly on reference

books, which fortunately are in ever increasing supply as relates to

historical and period architecture of all types. Only two or three

U.S. universities offer comprehensive courses in classical

production. We have a hazy idea about our ‘French country’, ‘English

Tudor’, ‘Mediterranean’, and ‘Contemporary’ styles, at least what the

recent spate of fashion designers interpret for our digestion. That

they are mostly woefully inadequate in proper execution is deplorable.

The fact remains that good period work is more costly and time

consuming to recreate than the half-baked 'transitional' styles

filling in. So little is produced that is truly first rate. Our

current ‘custom’ homes, generally merchant built notwithstanding, are

greatly distilled and stripped-down variations of true period

architecture.

Vanderbilt’s

Biltmore in Asheville, North Carolina is an ideal example of

near-perfect period work. Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, this

sprawling estate was the culmination of hard experience and learning.

Hunt was one of a few Americans who attended the internationally

prestigious Paris school of fine arts (Beaux Arts) near the turn of

the century, France’s leading institution of the decorative arts. Here

he studied the Grand Manner by sketching entire buildings and

classical elements on site, by learning theories of proportion,

composition, principles of axial symmetry, and renderings of wondrous

imaginary projects consisting of palaces, public works, casinos,

bridges, fountains, and the like. In the atelier system Master was

able to transmit to the pupil as much as possible in terms of theory

and technique. Ancient and exemplary contemporary Buildings were

analyzed much like medical students dissecting the human body.

Vanderbilt’s

Biltmore in Asheville, North Carolina is an ideal example of

near-perfect period work. Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, this

sprawling estate was the culmination of hard experience and learning.

Hunt was one of a few Americans who attended the internationally

prestigious Paris school of fine arts (Beaux Arts) near the turn of

the century, France’s leading institution of the decorative arts. Here

he studied the Grand Manner by sketching entire buildings and

classical elements on site, by learning theories of proportion,

composition, principles of axial symmetry, and renderings of wondrous

imaginary projects consisting of palaces, public works, casinos,

bridges, fountains, and the like. In the atelier system Master was

able to transmit to the pupil as much as possible in terms of theory

and technique. Ancient and exemplary contemporary Buildings were

analyzed much like medical students dissecting the human body.

Biltmore

is a Renaissance French palace based on Francis I’s Fontainbleu. Hunt

cleverly retained all classical proportions and decorative details

while combining a masonry veneer with contemporary materials (cast in

place concrete walls, electricity, elevators, steel roof framing,

modern plumbing, etc.). While he had the ability to innovate ‘of his

time’ using these modern materials, he and his client instead realized

an exquisite masterpiece of American architecture. One cannot leave

Biltmore without feeling he or she was transported not only into the

1890’s but also to the French Renaissance. The effect is truly a

period style work of parallel detail, spirit, and grand conception in

terms of siting, massing, and proportion. But is it authentic enough?

And how does the workmanship and attention to detail compare with

anything built in this country after the mid-20th century? While

Biltmore was an extravagant expenditure, it achieved its ends

admirably and with precision and grace. But even the more modest

mansions that preceded it up to the turn of the century, had a more

convincing execution than any of our current work, primarily due to

the mostly academic approach taken -- even through the most eclectic

fashions. The architects were simply better trained and educated,

having traveled to the fountain source, thus able to make their own

'original' works truly unique in 'correct' period manner.

Biltmore

is a Renaissance French palace based on Francis I’s Fontainbleu. Hunt

cleverly retained all classical proportions and decorative details

while combining a masonry veneer with contemporary materials (cast in

place concrete walls, electricity, elevators, steel roof framing,

modern plumbing, etc.). While he had the ability to innovate ‘of his

time’ using these modern materials, he and his client instead realized

an exquisite masterpiece of American architecture. One cannot leave

Biltmore without feeling he or she was transported not only into the

1890’s but also to the French Renaissance. The effect is truly a

period style work of parallel detail, spirit, and grand conception in

terms of siting, massing, and proportion. But is it authentic enough?

And how does the workmanship and attention to detail compare with

anything built in this country after the mid-20th century? While

Biltmore was an extravagant expenditure, it achieved its ends

admirably and with precision and grace. But even the more modest

mansions that preceded it up to the turn of the century, had a more

convincing execution than any of our current work, primarily due to

the mostly academic approach taken -- even through the most eclectic

fashions. The architects were simply better trained and educated,

having traveled to the fountain source, thus able to make their own

'original' works truly unique in 'correct' period manner.

Authenticity

The American Renaissance was the time of the mid-19th century through

the 1920’s and 30’s when industrialists and merchant princes, the

Medici’s of art and architecture, produced this country’s highest

quality residences inspired by the glorious period styles derived from

gothic and Greco-Roman models. The originality displayed by the

prominent architects of the day, Carrére and Hastings, H.H.

Richardson, McKim, Mead & White, and Hunt were displayed in dazzling

compositions ranging from academic renditions to eclectic combinations

of several styles. Originality and creative exposition was evident in

either mode.

The American Renaissance was the time of the mid-19th century through

the 1920’s and 30’s when industrialists and merchant princes, the

Medici’s of art and architecture, produced this country’s highest

quality residences inspired by the glorious period styles derived from

gothic and Greco-Roman models. The originality displayed by the

prominent architects of the day, Carrére and Hastings, H.H.

Richardson, McKim, Mead & White, and Hunt were displayed in dazzling

compositions ranging from academic renditions to eclectic combinations

of several styles. Originality and creative exposition was evident in

either mode.

The search for the proper or universal style, and a truly

'American' architecture characterized this period. Current

practitioners of 'contemporary' styles owe their freedom to the

experimentation of these eclectic architects, who initially worked out

free-flowing plans clothed in period elements. Classical pediments

found their way on rambling elevations, gothic and Greek were mixed,

spindles and crockets were combined with Moorish arches.

To be authentic is to freeze a certain period and recreate as closely

as possible every aspect of a design, from its floor planning to

exterior massing and detail. As Gilliatt comes to the heart of the

matter: "Quite apart from considerations of budget and lifestyle, the

salient question must be exactly how far should you go in your

attempts to preserve or recreate the past?"

To be authentic is to freeze a certain period and recreate as closely

as possible every aspect of a design, from its floor planning to

exterior massing and detail. As Gilliatt comes to the heart of the

matter: "Quite apart from considerations of budget and lifestyle, the

salient question must be exactly how far should you go in your

attempts to preserve or recreate the past?"

We

obviously deviate from period work if we include the conveniences and

technological advances to designs developed before the advent of air

conditioning and central heating, convenient toilets and baths,

electricity, television and telephones (there were pull cords attached

to bells for a long time), and the separation of kitchen facilities.

-- Or do we? Again, would we be emulating the 'original', or the

manner in which a revivalist interpreted a particular style in his or

her own manners, in the spirit or their time? [This last phrase is the

philosophical basis of gestalt that the modernist jealously claims to

legitimize employing only the current technologies within the

socio/political/economic exigencies, characterizing that moment in

history -- even forecasting the future! No one may thus invoke the

past for any reason: it would not be of "our time"; such a move stands

to be verboten by zealous adherents.]

We

obviously deviate from period work if we include the conveniences and

technological advances to designs developed before the advent of air

conditioning and central heating, convenient toilets and baths,

electricity, television and telephones (there were pull cords attached

to bells for a long time), and the separation of kitchen facilities.

-- Or do we? Again, would we be emulating the 'original', or the

manner in which a revivalist interpreted a particular style in his or

her own manners, in the spirit or their time? [This last phrase is the

philosophical basis of gestalt that the modernist jealously claims to

legitimize employing only the current technologies within the

socio/political/economic exigencies, characterizing that moment in

history -- even forecasting the future! No one may thus invoke the

past for any reason: it would not be of "our time"; such a move stands

to be verboten by zealous adherents.]

This seeming faux pas, of incorporating many modern conveniences and

technological advances into an ancient form -- revivalist or not, can

be rationalized to some degree as long as we are careful about door

hardware, plumbing and electrical fixtures, cabinets and countertops

which must follow the particular details of the period. There remains

the great balance of the equation: heights of floor to ceilings,

disposition of spaces, architectural interior moldings, coloration and

materials, period windows and doors, exterior composition and

elements, roofline, and associated details. If one does not observe

these points, the attempt is not truly a period work, but an

eclecticism. We have rationalized the effort to achieve period style

unfortunately, the ends are a Diaspora of jarring and ill conceived

concoctions of a bit of

this

grafted to a bit of that, all justified under our current pluralist

maxim: for if a client may behave as he wishes, why can't the

architect? An abrogation of any rule results in chaos and overall

ugliness. The 'rules', developed over millennia in the 'original'

form, while revived through the centuries, are the basic guides to

follow even today. Period work is more careful and studied, yet

achieves a 'right' expression: it is learnable and its execution by a

conscientious, if not completely competent architect or designer, is

less harmful to the aesthetic sensibility and the built environment,

than the wholesale display of arrogant and ignorant individualism

tempered by whim alone. The latter effect parallels individual

exuberation in the art world, especially the ongoing wild

experimentation from the mid-20th century to present times.

this

grafted to a bit of that, all justified under our current pluralist

maxim: for if a client may behave as he wishes, why can't the

architect? An abrogation of any rule results in chaos and overall

ugliness. The 'rules', developed over millennia in the 'original'

form, while revived through the centuries, are the basic guides to

follow even today. Period work is more careful and studied, yet

achieves a 'right' expression: it is learnable and its execution by a

conscientious, if not completely competent architect or designer, is

less harmful to the aesthetic sensibility and the built environment,

than the wholesale display of arrogant and ignorant individualism

tempered by whim alone. The latter effect parallels individual

exuberation in the art world, especially the ongoing wild

experimentation from the mid-20th century to present times.

The Pluralist Mode

At

the first we must recognize some of the leading problems that today’s

design professionals have concocted -- the first being amorphous floor

plans, especially with the introduction of diagonals, curves, and

other visual tricks at first draft to make the ‘reading’ of the plan

interesting and exciting to their potential clients, before proceeding

with elevation studies. Since the ‘plan is the generator’ – modernist

archispeak, the typical approach is to secure approval of the perfect

layout from which an elevation is then concocted. If we look at

the plan of Palladio’s Villa Rotunda, we might feel bored about the

strict geometry throughout, especially compared to even our medium

sized ‘semi’-custom plans which reek of drafting melange.

At

the first we must recognize some of the leading problems that today’s

design professionals have concocted -- the first being amorphous floor

plans, especially with the introduction of diagonals, curves, and

other visual tricks at first draft to make the ‘reading’ of the plan

interesting and exciting to their potential clients, before proceeding

with elevation studies. Since the ‘plan is the generator’ – modernist

archispeak, the typical approach is to secure approval of the perfect

layout from which an elevation is then concocted. If we look at

the plan of Palladio’s Villa Rotunda, we might feel bored about the

strict geometry throughout, especially compared to even our medium

sized ‘semi’-custom plans which reek of drafting melange.

The 'plan' was studied obsessively by the students of the Beaux-Arts and the principles of symmetry, procession, axis, proportion, weight, and composition – shared in part by the development of the elevations as well -- as were applied in formal or classical buildings. Even the asymmetry of the gothic revival elevation has a logic derived from the plan, which contains elements of the above. The pure geometry of classicism includes the circle and square, while the octagon is more associated with the gothic. (The Temple of the Winds, at the base of the Parthenon, is one of our few classical precedents for employing the octagon.) Ellipses, half-circles, apses, barrel vaults, groin vaulting, rotated grids (evident in Roman palace construction but lost for many years until examined and recorded by archaeologists) and rectangular spaces often following mathematical ratios based on musical harmony and octaves, seconds, and third intervals – all were key in the development of the plan. It was during the eclecticism of the late 19th century that these principles were abrogated in the search for a democratic plan for the common man.

So

one must decide the level of period style one wishes to incorporate.

How archaeological do we wish to be; is being architecturally correct

important? What key elements can be retained before contemporary floor

planning disturbs our recipe? To what extent will eclecticism affect

the design? Do you believe in the principle of diligently recreating

the past or simply adapting the ‘feel’ of a bygone era into a

contemporary structure? The choice is clear, and considering the

enormous expense to faithfully create period style, it seems most opt

for a distilled version. My view is that the closer one achieves

period style, the more enduring and timeless the results. Investment

value is arguably greater.

So

one must decide the level of period style one wishes to incorporate.

How archaeological do we wish to be; is being architecturally correct

important? What key elements can be retained before contemporary floor

planning disturbs our recipe? To what extent will eclecticism affect

the design? Do you believe in the principle of diligently recreating

the past or simply adapting the ‘feel’ of a bygone era into a

contemporary structure? The choice is clear, and considering the

enormous expense to faithfully create period style, it seems most opt

for a distilled version. My view is that the closer one achieves

period style, the more enduring and timeless the results. Investment

value is arguably greater.

Considering

the plurality of our time, this issue has been dismissed by the art

intelligentsia as spurious. One does as one feels or believes,

irrespective of any particular theory or set of principles -- except,

maddeningly -- the pursuit of period style. The architecture of

tradition is one of observing precedence and honoring the work of the

past, especially what we have come to inherent in the Western

Tradition by way of the ‘ancients’. Rules of architecture are as

important to maintaining civility as rules of law. And .... both

professions have their loopholes and exculpatory clauses. The art

world has reveled in anarchy with obvious results including a general

degradation of effort, technique, quality, and substance. We have

achieved the empowerment of the individual, the apotheosis in our time

of the id, of Ayn Rand’s ideal. We have lost our collective heritage

in the rush for individual expression. It is more important to

exercise our unfettered imaginations than build on past achievement.

How ridiculous this notion is if applied to science or philosophy? The

following excerpt from an undergraduate essay further illustrates

problems of revivals, authentic and eclectic:

Considering

the plurality of our time, this issue has been dismissed by the art

intelligentsia as spurious. One does as one feels or believes,

irrespective of any particular theory or set of principles -- except,

maddeningly -- the pursuit of period style. The architecture of

tradition is one of observing precedence and honoring the work of the

past, especially what we have come to inherent in the Western

Tradition by way of the ‘ancients’. Rules of architecture are as

important to maintaining civility as rules of law. And .... both

professions have their loopholes and exculpatory clauses. The art

world has reveled in anarchy with obvious results including a general

degradation of effort, technique, quality, and substance. We have

achieved the empowerment of the individual, the apotheosis in our time

of the id, of Ayn Rand’s ideal. We have lost our collective heritage

in the rush for individual expression. It is more important to

exercise our unfettered imaginations than build on past achievement.

How ridiculous this notion is if applied to science or philosophy? The

following excerpt from an undergraduate essay further illustrates

problems of revivals, authentic and eclectic:

I am still not sure what is the difference between a style, a revival of that style and an academic eclecticist version. Perhaps a revival tries to reproduce the original and an academic eclecticist version merely tries to make associations? It seems to me that every piece of architecture has to take something from the past. It's hard to do something totally new after three thousand years of building has already occurred.

I thought academic eclecticism might be a logical conclusion to the problem of style (i.e., what style is it? Is it original or a copy of something else?) because if it is subtle, it is style-less. If this movement is the culmination of all styles (which I thought maybe it would be) how do we account for the work of Le Corbusier and others who followed who did not want to have any historical associations?(Barbara Craven ,1997)

Period designoffers the basic building blocks from which any generation can improvise. When we have seen one temple front, we have not seen them all. To take the argument to its extreme: imagine a village, town, city, and domestic architecture either based on gothic and classical precedent or the same completely conceived laissez-faire a la modern, post-modern, decon or what have you. Is rampant artistic freedom worth the loss of order of any kind, of a kindred style betwixt the individual parts? The former model might be the city of Bath or any town that retains its historical past, especially the style of forefathers who built before the great disappointment of modern times and the horror of world war. The latter model is a reflection of chaos and nihilism, of a psychopathic culture. The post war suburbs in Zagreb, the public housing projects in Chicago, the concrete jungles of Houston and Los Angeles, the deadening effect of the New Berlin, all epitomize a mandate zealously promoted, but whose physical manifestations have created the ugliest, most miserable private and public places history has witnessed to date.

To acquiesce to period style of late however, is quite chic. But the academic world cannot quite shake off its status quo dogma inherited from the moderns. So we find individual practitioners bucking the establishment, while reviving the beauty of past styles. (Odd, the role reversal!) Their work is quiet, since the mass media is slow or fearful of making their case too strong: it is not progressive, it is not new -- only fashionable. The movement toward traditional architecture and urban planning (‘New Urbanism’) has gained momentum, and perhaps the time of a second Renaissance in this country is near. There is no doubt we are seeing a return to tradition.

"We talk of creativity and the future, but we ignore the discipline of learning the rudiments of the past. I maintain that the past is our most important source of creativity. True creativity is always the acquisition of the old in order to fashion beautiful and meaningful things for the present. If we wish not to be a culture marked by servility, a terrible intellectual and moral error born in the absence of creativity, we must conserve the past. Tradition is, as the philosopher Josef Pieper viewed it, a challenge." E. Christian Kopff, The Devil Knows Latin

For orders, general inquiries and billing matters: dreamhomedesignusa@mailback.com To contact Architect: johnhenryarchitect@gmail.com

Ultra Luxury Custom Homes, Villas and Estates by design

Copyright 1999/2000/2001 by John Henry Design International, Inc. All rights reserved.

Republication or re-dissemination of this site's content is expressly prohibited without the written permission of John Henry Design International, Inc.

John Henry Architect

MasterWorks Design International, Inc.

7491 Conroy Road

Orlando Florida 32835

TEL: 407 421 6647

EMAIL: johnhenryarchitect@gmail.com

Custom Home Design Services » Custom Home Remodeling » Luxury Home Interior Design Services » Custom Home Design Intro Offer »

About the Architect » Contact John Henry » Home Design Fee Schedule » Period Style House Design » How to Design Historic Mansions » Architect's Blog » Home Planner Ebook » Bibliography » Boxy But Good » Not So Big? Not So Smart »